Introduction

In modern manufacturing, precision is no longer optional—it is a fundamental requirement driven by increasingly complex product designs, shorter lead times, and the need for consistent quality across high-volume production. Among the most essential subtractive processes used to achieve these standards is machining milling, a versatile and highly controllable technique suitable for producing complex geometries across a wide range of materials. This technical guide explores how machining milling works, its core components, tooling principles, process optimization guidelines, and the latest advancements shaping next-generation manufacturing environments.

Whether applied in aerospace, automotive, mold making, or industrial engineering, machining milling continues to play a central role in shaping precision components that meet strict dimensional and performance criteria.

Understanding the Fundamentals of Machining Milling

Machining milling is a subtractive manufacturing process that removes material from a workpiece using rotary cutting tools. In this first section, the exact keyword machining milling appears as required. The process involves feeding the workpiece into a rotating cutter or moving the cutter across the workpiece to generate specific shapes, slots, pockets, and surface finishes. Milling machines operate based on a combination of movements along the X, Y, and Z axes, enabling operators or CNC systems to create multi-dimensional profiles with exceptional accuracy.

In technical environments, milling is categorized into several types—such as face milling, end milling, angular milling, and form milling—each chosen based on the geometry, tolerance requirements, and material characteristics of the component. Engineers rely on standardized cutting parameters like spindle speed, feed rate, tool diameter, and depth of cut to ensure optimal material removal while minimizing tool wear and vibration.

Key Components of Modern Milling Machines

A machining milling system consists of several integrated elements, each contributing to overall performance and output quality. The core components include:

Machine Structure:

The foundation—usually cast iron or reinforced steel—provides stability and vibration resistance, crucial for precision work.

Spindle Assembly:

The spindle drives the cutting tool. High-speed spindles, especially those capable of operating above 20,000 RPM, enable efficient machining of aluminum, composites, and other lightweight materials.

Worktable and Axis Drives:

The movement of the workpiece or tool along coordinated axes determines geometry accuracy. Advanced linear guides and ball screws reduce friction and increase positional precision.

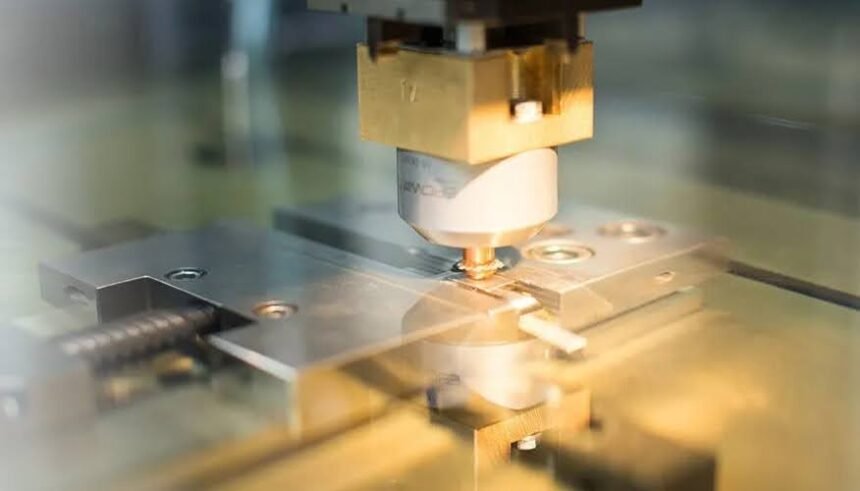

Tool Holder and Cutting Tools:

Tool holders secure the cutting tools, while carbide, HSS, or coated tools execute various milling operations. Tool selection is based on material hardness, thermal conductivity, and the expected surface finish.

Control System:

Modern milling machines use CNC controls, enabling automation, repeatability, and reduced human error. G-code programming guides toolpaths and machining strategies used in multi-axis systems.

Understanding these components is essential for technicians, operators, and engineers who aim to optimize machine performance, minimize downtime, and ensure consistent part quality.

Tooling Materials, Coatings, and Selection Criteria

Tooling is one of the defining factors in the success of machining milling operations. Cutting tools must withstand mechanical stress, heat generation, and abrasion while maintaining sharpness and dimensional stability.

Tooling Materials:

- Carbide: Common for high-speed machining due to its heat resistance and hardness.

- High-Speed Steel (HSS): More affordable and suitable for general milling but less wear-resistant.

- Ceramic & CBN: Used for machining hardened steels or high-temperature alloys.

Tool Coatings:

Coatings improve tool longevity and cutting performance. Popular options include TiN, TiAlN, DLC, and AlCrN. These coatings reduce friction, improve chip evacuation, and enable higher cutting temperatures.

Tool Selection Guidelines:

- Material Compatibility: Harder materials require robust tools and coatings.

- Chip Evacuation Needs: Tools with appropriate flute count help prevent clogging.

- Surface Finish Requirements: Finishing tools prioritize smoothness over aggressive cuts.

- Machine Capability: Tool size and geometry should align with spindle and tool holder limitations.

Proper tooling selection directly impacts efficiency, part accuracy, and operational cost savings.

Material Considerations in Machining Milling – With Reference to 91mns

Material selection plays a crucial role in determining machining parameters and tool wear. This section includes the second anchor text 91mns, exactly as required. Materials vary widely in hardness, tensile strength, ductility, and machinability rating, all influencing how milling operations should be planned.

For example, alloys like 91mns, steels, aluminum, titanium, brass, and plastics each present unique challenges. High-strength alloys may generate excessive heat, requiring coated carbide tools and optimized coolant strategies. On the other hand, softer materials like aluminum allow higher spindle speeds but require precise chip evacuation to avoid built-up edge (BUE).

Machinability ratings—often expressed relative to 100% machinability steel—help determine suitable feed rates and depth of cut. Materials with lower machinability require slower cutting speeds, increased lubrication, and tools with enhanced heat resistance. Engineers must carefully analyze these material properties before setting up the milling operation to prevent premature tool failure and dimensional inaccuracies.

Process Optimization Techniques for Improved Efficiency

Optimizing machining milling processes involves fine-tuning various parameters to achieve the ideal balance between speed, precision, and tool longevity. Key optimization strategies include:

Adaptive Feed Rate Control:

Modern CNC systems adjust feed rates automatically based on cutting load, preventing chatter and tool breakage.

High-Efficiency Milling (HEM):

HEM strategies rely on constant chip load, stepover control, and higher axial depths to maximize material removal while reducing tool stress.

Coolant Strategy Optimization:

Coolants—whether flood, mist, or through-tool—lower cutting temperatures and help evacuate chips. Proper coolant selection improves surface quality and extends tool life.

Toolpath Simulation:

Using CAD/CAM simulation prevents collisions, predicts cycle time, and identifies potential tool engagement issues before machining begins.

Vibration Control:

Stable fixturing, dampened tool holders, and balanced cutters help reduce vibrations that can compromise accuracy.

Predictive Maintenance:

Monitoring spindle load, bearing temperature, and tool wear data helps schedule proactive maintenance and prevents unexpected downtime.

Through these techniques, manufacturers reduce cycle time, increase output, and maintain consistent part quality.

Emerging Technologies Advancing Machining Milling

Advancements in machining milling continue to reshape the manufacturing landscape. Several innovations stand out:

Multi-Axis Milling:

Five-axis machines allow the creation of complex geometries without multiple setups, improving consistency and reducing labor time.

Digital Twin Technology:

Digital twins simulate the entire machining process using real-time data, enabling predictive optimization and rapid troubleshooting.

AI-Driven Process Control:

Artificial intelligence analyzes tool wear, cutting load, and machine vibrations, adjusting parameters automatically to ensure stable machining conditions.

Hybrid Manufacturing Systems:

Combining additive manufacturing with machining milling enables the production of near-net-shape components that are finished to precision tolerances using milling tools.

Advanced Tool Monitoring Sensors:

Integrated sensors automatically detect tool breakage, vibration spikes, or thermal overload, triggering corrective actions in real time.

These innovations not only streamline production but also help organizations stay competitive in global manufacturing markets.

Conclusion – Driving Precision Forward with Machining Milling

Machining milling remains a foundational process in precision manufacturing, offering high accuracy, geometrical flexibility, and compatibility with a vast range of materials and applications. From understanding machine components to selecting the right tools, optimizing parameters, and adopting emerging technologies, engineers and technicians can significantly enhance production efficiency and output quality.

Manufacturing professionals looking to improve their machining performance, upgrade their milling capabilities, or integrate advanced automation solutions are encouraged to explore modern CNC technologies, invest in skilled operator training, and adopt data-driven optimization methods. Start transforming your machining processes today by implementing the best practices outlined in this technical guide.